Medic – Mecklenburg County’s Public Health Superheroes

by: Julia Stullken, Master of Public Health student, and Dr. Jan Warren-Findlow, MPH Program Director and Associate Professor in the Department of Public Health Sciences

A recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in 2018 is critical of Emergency Medical Services (EMS) response times and how they differ across socioeconomic status (SES) for cardiac arrest cases.

The researchers found that in low income zip codes, the total time from EMS dispatch to arrival at the hospital was 5.5 minutes longer than that of high income areas. When it comes to cardiac arrest, time is crucial because each minute that the victim goes without treatment the risk of death increases. The researchers also placed high importance on the amount of time spent on the scene (from the time EMS arrives to the time they depart for the hospital). They argue that additional time spent on the scene could be attributed to scene safety or language barriers, and is detrimental to patients.

After reading this study, our natural next question was “How is Mecklenburg County doing with EMS response times?” We toured the Mecklenburg County EMS Agency (Medic) facility led by Lester Oliva, Public Information Specialist and Paramedic. Medic services an area of over 500 square miles with more than 100 vehicles. They responded to approximately 150,000 calls in 2018, which is 7% more calls than the previous year. Medic has meticulous data collection and they take safety, efficiency and quality improvement very seriously. But how do they measure up to national standards? Extremely well, it turns out.

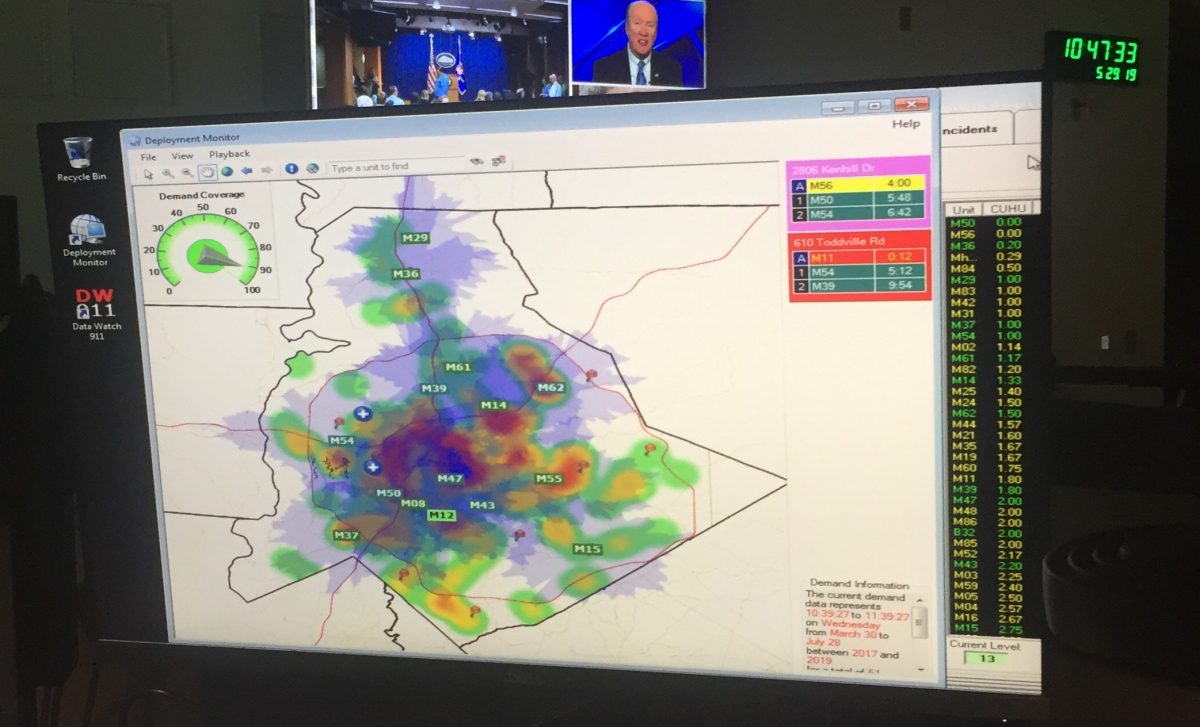

Medic follows – and in many cases surpasses – national benchmarks for all types of cases, but we will focus on cardiac arrest cases here. Medic maintains strict standards for time-to-scene and time-on-scene, ensuring that regardless of zip code, they respond to all calls in as little time as possible. They are able to do this because they’ve adopted a mobile response model rather than a static one – meaning ambulances are stationed around the county based on where the highest predicted need will be.

MEDIC uses a sophisticated health informatics model to predict possible emergency sites based on traffic, weather patterns, and scheduled events. Using this approach is beneficial in multiple ways because it ensures that there is at least one ambulance within a ten minute radius of any location in Mecklenburg County; and it maximizes the amount of time each paramedic has to spend with patients rather than in route or in traffic.

Many smaller EMS agencies use static stations, meaning that all ambulances are dispatched from a central location, but this can increase the time-to-scene for lower income or rural areas. Medic is able to consistently respond to 911 calls in 10 minutes or less.

Above: An example of the informatics software that dispatchers at Medic use to determine where ambulances will be most needed.

Time-to-scene is not the only important factor though – what about once the ambulance arrives? The JAMA article mentioned earlier argues that longer time on scene could be related to worse outcomes for patients. However, the time spent on the scene is important for another reason – the treatment the patient receives in the first minutes after cardiac arrest can greatly impact survival.

For this reason, Medic spends a mandatory 20 minutes with cardiac arrest victims once they arrive to resuscitate and stabilize them. All trucks are equipped with the tools necessary to administer life-saving treatment after cardiac arrest.

In addition to cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and automatic external defibrillator (AED) to treat cardiac arrest, they also use an approach called mild therapeutic hypothermia, which is a way of using cold fluids to reduce body temperature and prevent neurological damage to the brain for patients who do not regain consciousness after resuscitation. The technique was originally developed for use in the hospital, but has since been adopted by EMS to improve outcomes after cardiac arrest.

These protocols are achieving results: last year 81% of Medic patients in cardiac arrest achieved return of spontaneous circulation – that puts Medic in the top 1% in the nation.

The recipe for success begins before cardiac arrest occurs. Prevention is a large part of Medic’s plan for continued improvement.

Their Quality Improvement Department (staffed with several UNC Charlotte MPH/MSPH alumnae) works behind the scenes to ensure that what goes on in the field is achieving the desired results. Not only do they perform research in the field to find ways to improve safety and patient outcomes, they also participate in extensive community outreach and education.

One way Medic is improving cardiac arrest outcomes is by educating the community in bystander CPR with the Keep the Beat campaign (a joint effort between Atrium Health, Novant Health, and Medic). Bystander CPR is a hands-only method of performing CPR that requires no certification and could save someone’s life. Medic provides free training in bystander CPR to any Mecklenburg County business or organization. The Keep the Beat campaign also involves the launch of the PulsePoint application in Mecklenburg County. The application notifies CPR-trained bystanders within a quarter mile radius of cardiac emergencies that have occurred in public spaces and instructs them where to find the nearest AED.

During the spring 2019 semester, students in the Graduate Public Health Association participated in Keep the Beat’s bystander CPR training (led by MPH alumna, Gabby Purick), and are now confident they could perform hands-only CPR if needed. We did it and so can you!

If you or your team are interested in scheduling a free bystander CPR training session, visit KeeptheBeatMeck.com.

For more information about Medic, you can also read this article in the Journal of Emergency Services.

Acknowledgments and Sources:

Lester Oliva, Public Information Specialist & Paramedic, Medic